Семантические группы существительных singularia и pluralia tantum виноградов конспект

Обновлено: 05.07.2024

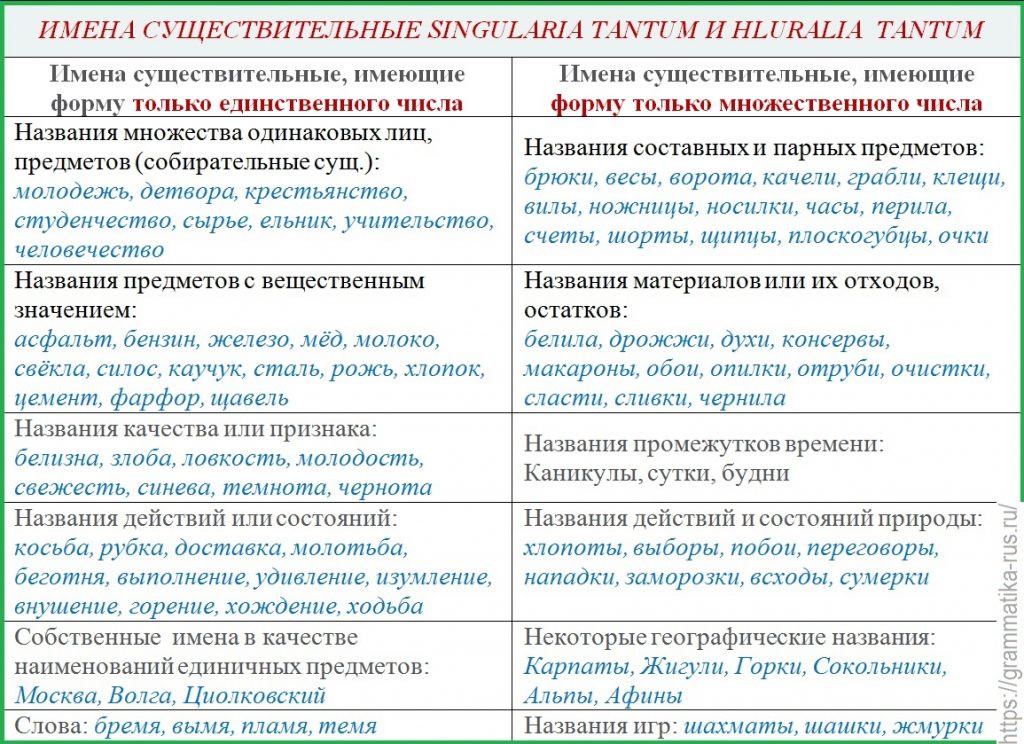

Как носители категории числа все существительные делятся на слова: имеющие формы единственного и множественного числа, имеющие только формы единственного числа (или преимущественно употребляющиеся в формах ед. ч.) – существительные singularia tantum (собирательные сущ., некоторые вещественные сущ., некоторые абстрактные сущ., наименования единичных предметов);

и имеющие только формы множественного числа – существительные pluralia tantum (названия парных предметов, некоторые вещественные и абстрактные сущ. названия промежутков времени, некоторые географические названия).

Существительные pluralia tantum не имеют морфологического значения рода, так как нет ед.ч.

© Авторские права2022 Русский язык без проблем. Rara Academic | Developed By Rara Theme. Работает на WordPress.

Лекции

Лабораторные

Справочники

Эссе

Вопросы

Стандарты

Программы

Дипломные

Курсовые

Помогалки

Графические

Доступные файлы (1):

Key terms: biological sex, gender, gender agreement, formal category, meaningful category, gender classifiers, obligatory correlation, person nouns, non-person nouns, neuter gender, feminine nouns, masculine nouns, common gender, personification

Formal and functional peculiarities of the singular and the plural forms of nouns in English. Their oppositional presentation. The problem of singular and plural semantics for different groups of nouns. Relative and absolute number; the absolute singular (singularia tantum) number and the absolute plural (pluralia tantum) number. Oppositional reduction of the category for different groups of nouns.

Существительные singularia tantum обычно обозначают следующие референты: абстрактные понятия – love, hate, despair, и др.; названия веществ и материалов – snow, wine, sugar, и др.; отрасли профессиональной деятельности– politics, linguistics, mathematics; собирательные объекты – fruit, machinery, foliage и др. Есть и некоторые другие существительные singularia tantum, которые трудно классифицировать, например, advice, news и др. Как видно из приведенных примеров, сами эти существительные не обладают никакими признаками, позволяющими определить их как существительные singularia tantum: их форма может совпадать либо с формой единственного числа - advice, либо с формой множественного числа – news. Статус этих слов как существительных singularia tantum формально определяется по их сочетаемости, через отражение категории числа в примыкающих к ним словах: все существительные singularia tantum употребляются только с глаголами в единственном числе, они исключают употребление с числительным “one” и с неопределенным артиклем; их количество передается с помощью специальных лексических квантификаторов little, much, some, any, a piece, a bit, an item, например: an item of news, a piece of advice, a bit of joy. Как отмечалось ранее, этот способ передачи грамматического значения числа неисчисляемых существительных является настолько регулярным, что его можно рассматривать как периферийные супплетивные формы (см. Раздел № 3).

The absolute singular nouns usually denote the following referents: abstract notions – love, hate, despair, etc.; names of substances and materials – snow, wine, sugar, etc.; branches of professional activity – politics, linguistics, mathematics; some collective objects – fruit, machinery, foliage, etc. There are some other singularia tantum nouns, that are difficult to classify, e.g., advice, news and others. As the examples above show, the nouns themselves do not possess any formal marks of their singularia tantum status: their form may either coincide with the regular singular – advice, or with the regular plural – news. Their singularia tantum status is formally established in their combinability, being reflected by the adjacent words: all singularia tantum nouns are used with the verbs in the singular; they exclude the use of the numeral “one” or of the indefinite article. Their quantity is expressed with the help of special lexical quantifiers little, much, some, any, a piece, a bit, an item, e.g.: an item of news, a piece of advice, a bit of joy, etc. As mentioned earlier, this kind of rendering the grammatical meaning of number with uncountable nouns is so regular that it can be regarded as a marginal case of suppletivity (see Unit 3).

The absolute plural nouns usually denote the following: objects consisting of two halves – scissors, trousers, spectacles, etc.; some diseases and abnormal states – mumps, measles, creeps, hysterics, etc.; indefinite plurality, collective referents – earnings, police, cattle, etc. The nouns belonging to the pluralia tantum group are used with verbs in the plural; they cannot be combined with numerals, and their quantity is rendered by special lexical quantifiers a pair of, a case of, etc., e.g.: a pair of trousers, several cases of measles, etc.

In terms of the oppositional theory one can say that in the formation of the two subclasses of uncountable nouns, the number opposition is “constantly” (lexically) reduced either to the weak member (singularia tantum) or to the strong member (pluralia tantum). Absolute singular nouns or absolute plural nouns are “lexicalized” as separate words or as lexico-semantic variants of regular countable nouns. For example: a hair as a countable noun denotes “a threadlike growth from the skin” as in I found a woman’s hair on my husband’s jacket; hair as an uncountable noun denotes a mass of hairs, as in Her hair was long and curly. Similar cases of oppositional neutralization take place when countable nouns are used in the absolute singular form to express the corresponding abstract ideas, e.g.: to burst into song; or the material correlated with the countable referent, e.g.: chicken soup; or to express generic meaning, e.g.: The rose is my favourite flower (=Roses are my favourite flowers). The opposite process of the restoration of the number category to its full oppositional force takes place when uncountable nouns develop lexico-semantic variants denoting either various sorts of materials (silks, wines), or manifestations of feelings (What a joy!), or the reasons of various feelings (pleasures of life – all the good things that make life pleasant), etc.

Lexicalization of the absolute plural form of the noun can be illustrated with the following examples: colours as an absolute plural noun denotes “a flag”; attentions denotes “wooing, act of love and respect”, etc. Oppositional neutralization also takes place when regular countable collective nouns are used in the absolute plural to denote a certain multitude as potentially divisible, e.g.: The jury were unanimous in their verdict. Cases of expressive transposition are stylistically marked, when singularia tantum nouns are used in the plural to emphasize the infinite quantity of substances, e.g.: the waters of the ocean, the sands of the desert, etc. This variety of the absolute plural may be called “descriptive uncountable plural”. A similar stylistically marked meaning of large quantities intensely presented is rendered by countable nouns in repetition groups, e.g.: cigarette after cigarette, thousand upon thousand, tons and tons, etc. This variety of the absolute plural, “repetition plural” can be considered a specific marginal analytical number form.

The problem of the category of case in English. Various approaches to the category of case in English language study: “the theory of positional cases”, “the theory of prepositional cases”, “the theory of limited case”, “the theory of possessive postposition” ("the theory of no case"); their critical assessment. Disintegration of the inflexional case in the course of the historical development of English and establishing of particle case forms. Formal and functional properties of the common case and the genitive case. The word genitive and the phrase genitive. The semantic types of the genitive. The correlation of the nounal case and the pronounal case.

The category of case in English constitutes a great linguistic problem. Linguists argue, first, whether the category of case really exists in modern English, and, second, if it does exist, how many case forms of the noun can be distinguished in English. The main disagreements concern the grammatical status of “noun + an apostrophe + –s” form (Ted’s book, the chairman’s decision) rendering the same meaning of appurtenance as the unfeatured form of the noun in a prepositional construction, cf.: the chairman’s decision – the decision of the chairman.

The following four approaches, advanced at various times by different scholars, can be distinguished in the analysis of this problem.

The solution to the problem of the category of case in English can be formulated on the basis of the two theories, “the theory of limited case” and “the theory of the possessive postpositive”, critically revised and combined. There is no doubt that the inflectional case of the noun in English has ceased to exist. The particle nature of –‘s is evident, since it can be added to units larger than the word, but this does not prove the absence of the category of case: it is a specific particle expression of case which can be likened to the particle expression of the category of mood in Russian, cf.: Я бы пошел с тобой. A new, peculiar category of case has developed in modern English: it is realized by the paradigmatic opposition of the unmarked “direct”, or “common” case form and the only “oblique” case form: the genitive marked by the possessive postpositional particle. Two subtypes of the genitive are to be recognized: the word genitive (the principal type) and the phrase genitive (the minor type). Since similar meanings can be rendered in English by prepositional constructions, the genitive may be regarded as subsidiary to the syntactic system of prepositional phrases; still, the semantic differences between them and their complementary uses sustain the preservation of the particle genitive in the systemic expression of nounal relations in English.

родительный обладателя (неорганического обладания), например: Tom’s toy; этот тип значения может быть продемонстрирован (эксплицирован) с помощью следующего трансформационного диагностического теста: Tom’s toythe toy belongs to Tom;

родительный целого(органического обладания), например: Tom’s handthe hand is a part of Tom; в качестве подтипа можно выделить родительный приобретенного качества, например: Tom’s vanityvanity is the peculiar feature of Tom;

родительный агента действия(субъекта действия), например: Tom’s actionsTom acts; в качестве подтипа можно выделить родительный автора, например: Dickens’s novelsthe novels written by Dickens;

родительныйпациенса(объектадействия), например: the hostages’ releasethe hostages were released;

родительный предназначения, например: women’s underwearunderwear for women;

родительныйкачества, например: a girl’s voicethe voice characteristic of a girl, peculiar to a girl; подтип - родительныйсравнения, например: a cock’s self-confidenceself-confidence like that of a cock, resembling the self-confidence of a cock;

адвербиальный родительный (обычно для определения обстоятельств места и времени), например: yesterday’s talksthe talks that took place yesterday;

родительный количества, например: athree miles’distance from here.

the genitive of possessor (of inorganic possession), e.g.: Tom’s toy; this type of meaning can be explicitly demonstrated by a special transformational diagnostic test: Tom’s toythe toy belongs to Tom;

the genitive of the whole (of organic possession), e.g.: Tom’s handthe hand is a part of Tom; as a subtype the genitive of received qualification can be distinguished, e.g.: Tom’s vanityvanity is the peculiar feature of Tom;

the genitive of agent, or subject of action, e.g.: Tom’s actionsTom acts; the minor subtype of this is the genitive of author, e.g.: Dickens’s novelsthe novels written by Dickens;

the genitive of patient, or object of action, e.g.: the hostages’ releasethe hostages were released;

the genitive of destination, e.g.: women’s underwearunderwear for women;

the genitive of qualification, e.g.: a girl’s voicethe voice characteristic of a girl, peculiar to a girl; subtype – the genitive of comparison, e.g.: a cock’s self-confidenceself-confidence like that of a cock, resembling the self-confidence of a cock;

the adverbial genitive (usually of place and time modification), e.g.: yesterday’s talksthe talks that took place yesterday;

the genitive of quantity, e.g.: a three miles’ distance from here.- План конспект нетрадиционного урока в спо

- Связь поколений в традициях городца изо 4 класс конспект урока и презентация

- Веселые стихи заходера 1 класс конспект

- Конспект занятия различение наложенных изображений предметов

- Соотношения между сторонами и углами прямоугольного треугольника 8 класс конспект урока

Приведенное семантическое описание родительного падежа не является исчерпывающим; оно допускает дальнейшие подразделения и объединения семантических типов. Иногда все значения родительного падежа в английском языке объединяют в две большие группы: обозначающие обладание и обозначающие качество. Такое разделение существенно с точки зрения грамматики, поскольку в первом случае артикли и определения, стоящие перед словосочетанием относятся к существительному в родительном падеже, например: the young man’s son, Byron’s last poem, а во втором случае – к определяемому второму существительному, например: a pleasant five minutes walk.

The given semantic description of the genitive is not exhaustive; there may be further subdivisions and generalizations. Sometimes all the semantic types of the genitive are united into two large groups: those denoting possession and those denoting qualification. This subdivision is grammatically relevant, because in the first case the articles and attributes modify the noun in the genitive case itself, e.g.: the young man’s son, Byron’s last poem, while in the second case they modify the noun which follows the one in the genitive case, e.g.: a pleasant five minutes’ walk.

As is clear from the description given, the genitive does not always denote “possession”; that is why the term “genitive” is more accurate than the term “possessive”, though both of them are widely used in linguistics.

В истории лингвистики были попытки использовать соотношение систем падежных форм местоимения и существительного, чтобы доказать существование категории падежа существительных или ее отсутствие. Однако, ни признание местоименного падежа, ни его отрицание не могут доказать существование или отсутствие категории падежа у существительного: категория падежа существительного не может рассматриваться как зависящая от падежа местоимения, поскольку местоимения замещают существительные и отражают их категории, а не наоборот.

There were attempts in the history of linguistics to use the correlation of the pronounal case system and the nounal case system to prove the existence or the absence of the category of case of nouns. But neither the acceptance of the pronounal case nor its rejection can prove the existence or the absence of the nounal case category: the category of case of nouns cannot be treated as depending upon the case system of pronouns, since pronouns substitute for nouns, reflecting their categories, and not vice versa.

19. Числовая корреляция. Существительные с полной и дефектной числовой парадигмой. Типы слов singularia и pluralia tantum.

Далеко не все существительные имеют формы обоих чисел. Сле¬довательно, категория числа должна быть отнесена к группе непос¬ледовательно коррелятивных категорий. Слова, не имеющие форм множественного числа, называются существительными singularia tantum, что в переводе с латинского означает буквально 'только фор¬мы ед.ч'. К числу singularia tantum относятся многие отвлеченные существительные: бег, тишина, перемирие; вещественные: олово, мо¬локо, сахар; собирательные: листва, пролетариат, человечество; не¬которые имена собственные: Енисей, Крым, Зевс и др. (к последней группе примыкают названия ряда спортивных и иных игр: футбол, хоккей, преферанс).

Бывают также существительные, не имеющие формы единствен¬ного числа (pluralia tantum 'только формы мн.ч.'). К ним также от¬носятся некоторые отвлеченные существительные: поминки, пере¬говоры, хлопоты; вещественные: духи, сливки, чернила; собиратель¬ные: деньги, джунгли, финансы; многие имена собственные: Альпы, Лужники, Мытищи; сюда же примыкают и названия детских и спортивных игр: казаки-разбойники, прятки, пятнашки, шахматы и др.; особую группу составляют конкретные существительные типа брюки, ворота, ножницы, сани и др.

В результате сравнения существительных singularia tantum и pluralia tantum нетрудно заметить, что образованию соотноситель¬ных числовых форм в обоих случаях препятствует один и тот же фак¬тор — особенности лексической семантики существительного, т.е. принадлежность имени к определенным лексико-грамматическим разрядам существительных: отвлеченных, вещественных, собира¬тельных или собственных. Конкретные же существительные обыч¬но имеют обе числовые формы: булка — булки, стол — столы, озеро — озёра. Исключение составляют лишь немногочисленные слова pluralia tantum типа сани; эти существительные обозначают предме¬ты, имеющие сложное, нередко парное строение (ср.: брюки, воро¬та, очки, ножницы); у многих из них некогда существовала форма единственного числа, которая с развитием языка была утрачена.

От некоторых существительных singularia tantum в профессио¬нальном языке, в разговорной речи и языке поэзии иногда образу¬ется, вопреки отмеченной выше закономерности, форма множе¬ственного числа. В таком случае она имеет некоторые особенности семантики по сравнению с формой множественного числа конкрет¬ных существительных.

Самое важное в русском языке - это знать род существительного (ОН, ОНА или ОНО).

Мы уже обсуждали, как легко сделать из единственного числа множественное (кто не помнит, может посмотреть здесь).

Сегодня вы узнаете о существительных, которые могут быть либо только в единственном числе (или singularia tantum), либо только во множественном числе (или pluralia tantum).

SINGULARIA tantum (существительные только в единственном числе)

Э́то моё зо́лото. Я купи́ла его́ в ювели́рном магази́не.

Читайте также: